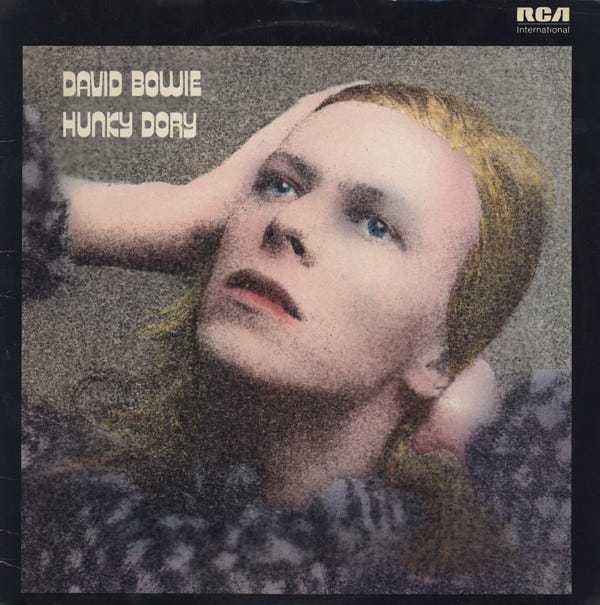

[Archive] A Glimpse of 'Hunky Dory' by David Bowie

The sound of David finding his inner Bowie.

As a reminder, I’m revisiting (and lightly revising) some posts from my archive for the next few weeks while I complete a book project. All the posts I’m selecting are normally behind a paywall. I’ll post a new Gems playlist as usual on the weekend.

Listen via Spotify | Apple Music

Hunky Dory came in a golden moment for Bowie, and - wow - he took advantag…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to LP to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.